Biography

My long career as a researcher and educator began on a secluded northern New Mexico plateau where the Manhattan Project had developed the atomic weapons that the United States used to end World War II and influence subsequent decades.  My formative years were largely confined in this fenced town that the government built for the scientists and technicians of the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory. Even while confined within the fences surrounding the oft-called “secret city” of Los Alamos, however, I would develop an unquenchable curiosity about the outside world.

My formative years were largely confined in this fenced town that the government built for the scientists and technicians of the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory. Even while confined within the fences surrounding the oft-called “secret city” of Los Alamos, however, I would develop an unquenchable curiosity about the outside world.

I would only gradually learn about the historical circumstances that enabled my family to become the first black residents of Los Alamos. I discovered that my grandfather, Edward Carson, was among the millions of black migrants who left the South to seek industrial jobs in northern cities, in his case leaving Tuscaloosa, Alabama, and traveling to Detroit where he secured a lasting job at Ford Motor Company. His son, Clayborne Carson, Sr., would grow up in a stable family, graduate from Northwestern High School, and even later take a few classes at Wayne State University. Dad’s initial employment featured summer work as a cabin steward paid $125 a month helping tourists on the Lake Steamers sailing between Detroit and Canadian ports.

His life took an unexpected turn, however, when the United States entered World War II.

After the Army drafted him, tests determined that he was suitable for officer training which took place at Maxwell Air Base in Montgomery, Alabama. There he met and soon married Louise Lee, who had migrated from rural north Florida to Montgomery to find a job and (perhaps unexpectedly) a husband among the black soldiers training at the nearby military base. I never learned the details of their marriage, but Dad’s military records would inform me that when I was born in June 1944, while Mom was staying with her relatives in Buffalo, he was in France commanding a black platoon in the racially segregated troops participating in the Allied invasion that defeated Nazi forces in France and Germany. After First Lieutenant Carson returned to the United States in November 1945, he joined Mom and me in Seattle.

After the Army drafted him, tests determined that he was suitable for officer training which took place at Maxwell Air Base in Montgomery, Alabama. There he met and soon married Louise Lee, who had migrated from rural north Florida to Montgomery to find a job and (perhaps unexpectedly) a husband among the black soldiers training at the nearby military base. I never learned the details of their marriage, but Dad’s military records would inform me that when I was born in June 1944, while Mom was staying with her relatives in Buffalo, he was in France commanding a black platoon in the racially segregated troops participating in the Allied invasion that defeated Nazi forces in France and Germany. After First Lieutenant Carson returned to the United States in November 1945, he joined Mom and me in Seattle.

I was too young to retain memories of my early family life but later determined that Dad’s military experience prompted the newly formed Atomic Energy Commission to hire him as the first black security inspector at Los Alamos. For several years we rented housing nearby Los Alamos, but in 1949 my two younger siblings and I moved into a newly-built two-story rental with three bedrooms and a spacious year.

I realized that the town’s more affluent residents lived in older neighborhoods featuring single-family housing, but our place had its own appeal only a street away from the mountains on the edge of Los Alamos. The house became our long-term home, and the nearby forest offered occasional solitary refuge. I became aware that more affluent residents lived in somewhat older neighborhoods with nicer single-family housing. I couldn’t ignore news articles about civil rights protests elsewhere in the United States but was content with the high-quality public school system in Los Alamos that provided the basic skills needed to become a successful college student, a skillful researcher, and ultimately an expert writer. As I became old enough to take summer jobs at the Lab, I wanted to learn more about the scientific innovations that had been made. Although I felt comfortable as the only black student in nearly all my classes I realized that the fences protecting Los Alamos also confined me. I wanted to know more about the Little Rock Nine, the lunch counter protesters, and the freedom riders.

After finishing high school in June 1962, I enrolled in the University of New Mexico’s Honors Program at the University of New Mexico and immersed myself in campus politics as well as diverse classes in the sciences and humanities. My increasing interest in the civil rights movement led me to attend the 1963 National Student Association conference at the University of Indiana.  There I met Stokely Carmichael, a Howard University student seeking NSA’s support for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee’s voting rights campaign as well as the upcoming March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Despite Carmichael’s dismissal of the March as merely a “picnic” when compared to SNCC’s projects, I joined a group of civil rights proponents who chartered a bus ride to the March, where I joined a crowd about the size of New Mexico’s entire population. I admired Martin Luther King’s historic concluding oration but was also intrigued by the earlier audacious prediction by SNCC’s John Lewis that “the day will come when we will not confine our marching to Washington.”

There I met Stokely Carmichael, a Howard University student seeking NSA’s support for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee’s voting rights campaign as well as the upcoming March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Despite Carmichael’s dismissal of the March as merely a “picnic” when compared to SNCC’s projects, I joined a group of civil rights proponents who chartered a bus ride to the March, where I joined a crowd about the size of New Mexico’s entire population. I admired Martin Luther King’s historic concluding oration but was also intrigued by the earlier audacious prediction by SNCC’s John Lewis that “the day will come when we will not confine our marching to Washington.”

After returning to New Mexico, I was still eager to explore the rest of the world. I considered volunteering for SNCC’s 1964 Mississippi Summer Project but learned that even volunteers were expected to support themselves. I trained for a Peace Corps program in Brazil but was unexpectedly rejected.

I then accepted my older sister’s invitation to join her in Los Angeles where I enrolled at UCLA, secured a job as a computer programmer, and used my “free time” to protest for civil rights reforms and ending America’s military intervention in Vietnam.

My attraction to the local Non-Violent Action Committee (N-VAC) prompted me to write a profile in the Los Angeles Free Press on the group’s co-founder Woody Coleman, who accurately warned that Los Angeles would experience a racial “bloodbath” during the summer of 1965. Because freelance journalism offered an appealing way to explore my new urban setting, I welcomed opportunities to write profiles and news articles for the Free Press and various other local publications.

As I became increasingly involved in protests against the war in Vietnam, I also realized that I was likely to be drafted after my graduation from UCLA in June 1967. After my application for conscientious objector status was rejected, I discussed my options with my girlfriend Susan Beyer, who had graduated with me from UCLA, and we decided to marry and then leave in October 1967 for an expected long exile in Europe. With our combined savings, we traveled through western Europe during the Fall and Winter, but when Susan became severely ill with diabetes during the spring of 1968, we returned to Los Angeles. While still seeking to avoid the military draft, I fortunately became a computer programmer at UCLA’s Survey Research Center.

As I became increasingly involved in protests against the war in Vietnam, I also realized that I was likely to be drafted after my graduation from UCLA in June 1967. After my application for conscientious objector status was rejected, I discussed my options with my girlfriend Susan Beyer, who had graduated with me from UCLA, and we decided to marry and then leave in October 1967 for an expected long exile in Europe. With our combined savings, we traveled through western Europe during the Fall and Winter, but when Susan became severely ill with diabetes during the spring of 1968, we returned to Los Angeles. While still seeking to avoid the military draft, I fortunately became a computer programmer at UCLA’s Survey Research Center.

Following the assassination that spring of Martin Luther King and the resulting nationwide protests, I volunteered to help UCLA professor Gary Nash and other scholars develop new courses on American racial relations. This collaboration soon prompted me to combine my computer research with historical research and eventually graduate-level courses in the history department. After completing two years of graduate courses, I resigned from my computer job to focus on additional historical research.

I then traveled throughout the United States to interview SNCC organizers and leaders such as John Lewis and Stokely Carmichael. This research led UCLA to hire me as an “acting assistant professor.” By the time I earned a UCLA doctorate in history in 1975, my extensive research, diverse publications, and innovative teaching had prompted Stanford University to select me for its faculty. This research would eventually become the basis for my doctoral dissertation and initial book, In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening, published by Harvard University Press in 1981. The following year, my study won the Organization of American Historian’s Frederick Jackson Turner Award in 1982 as the best first book by an American historian. After becoming a tenured Associate Professor at Stanford, I began teaching not only African American history but eventually pioneering courses on urban and labor history as well as a controversial interdisciplinary course “Western Culture: An Alternative View.

In January 1985, Coretta Scott King, founding director of the King Center in Atlanta, called to ask me to direct a long-term effort to publish the writings and statements of her late husband. After intense negotiations with her, I recruited a research team to assemble and publish a multi-volume edition of The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr. I also arranged for Coretta’s initial visit to meet with Stanford officials and my colleagues in November 1986. The King Papers Project innovatively used computers to catalog thousands of King-related documents and audio-visual materials.

In January 1985, Coretta Scott King, founding director of the King Center in Atlanta, called to ask me to direct a long-term effort to publish the writings and statements of her late husband. After intense negotiations with her, I recruited a research team to assemble and publish a multi-volume edition of The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr. I also arranged for Coretta’s initial visit to meet with Stanford officials and my colleagues in November 1986. The King Papers Project innovatively used computers to catalog thousands of King-related documents and audio-visual materials.

Even while becoming more familiar with King’s singular oratory, my lectures, and academic writings still depicted him as a “charismatic leader in a mass movement in which ideas disseminated from the bottom up as well as from the top down.”

Even while becoming more familiar with King’s singular oratory, my lectures, and academic writings still depicted him as a “charismatic leader in a mass movement in which ideas disseminated from the bottom up as well as from the top down.”

While I focused on King-related research, one of my graduate seminars also inspired Malcolm X: The FBI File (published in 1991). I also expanded my understanding of the civil rights movement through my experience as a senior scholarly advisor for the televised documentary series Eyes on the Prize (1987-1993) and co-editor of The Eyes on the Prize Civil Rights Reader (1991).

The King Papers Project’s discovery of plagiarized passages in King’s theological writings at Boston University enmeshed me in a highly-publicized controversy even before the publication early in 1992 of the first volume of The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr. I expressed his evolving views about King’s academic and early writings not only in The Papers but also in published interviews and scholarly articles. An Ebony magazine review acclaimed the first volume as “one of those rare publishing events that generate as much excitement in the cloistered confines of the academy as they do in the general public.”

The King Papers Project’s discovery of plagiarized passages in King’s theological writings at Boston University enmeshed me in a highly-publicized controversy even before the publication early in 1992 of the first volume of The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr. I expressed his evolving views about King’s academic and early writings not only in The Papers but also in published interviews and scholarly articles. An Ebony magazine review acclaimed the first volume as “one of those rare publishing events that generate as much excitement in the cloistered confines of the academy as they do in the general public.”

My research about King’s deep family roots in the Atlanta area also inspired a musical docudrama “Passages of Martin Luther King,” based on the King Institute’s autobiography documents assembled by the King Institute. After successful performances at Stanford in April 1993, other drama groups performed “Passages” at Dartmouth, Princeton, Willamette, Tacoma, and elsewhere in the United States.

“Passages” would eventually inspire foreign-language productions in Beijing, China, and the Palestinian West Bank that expanded my outreach to areas with little understanding of King’s ideas by exploring the global implications of King’s ideas. Each of these productions also inspired documentary films.

During the 1990s, the King Papers Project not only completed three more volumes of The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr. but also released its findings on a new Stanford website featuring King-related documents and a Liberation Curriculum with lesson plans and workshops for Bay Area high school teachers.

While editing new volumes of The Papers, I also published several articles for the Journal of American History as well as other writings. I also wrote my most widely circulated publication, The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr. (1998). This compilation of King’s autobiographical writings was later translated into more than a dozen languages. I also compiled King’s most notable sermons in A Knock at Midnight (1998) as well as his key speeches in A Call to Conscience (2001). While preparing these publications designed for specialized readers interested in King, I also co-wrote, with Emma Lapsansky and Gary Nash, African American Lives: The Struggle for Freedom (2005), the first of several editions of a comprehensive African-American history textbook, later retitled The Struggle for Freedom: A History of African Americans (2019).

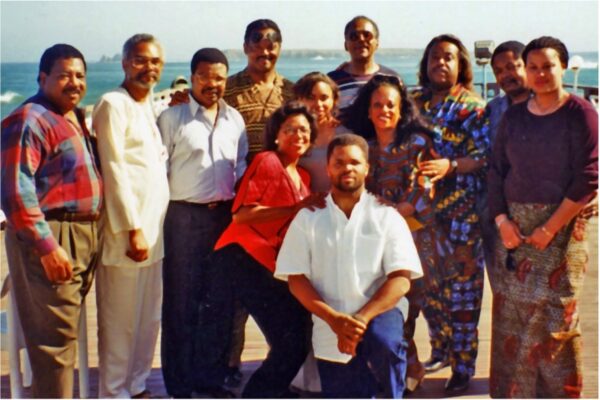

My increasingly varied publications during the project’s initial decade were also accompanied by international travels that broadened my understanding of the King’s global impact and the complex relationship between the civil rights struggle in the United States and post-colonial liberation movements, especially in Africa. When I was considering how to arrange a family vacation for my son, who was graduating from Howard University, and my daughter, who was graduating from San Jose State University, I sought advice from former SNCC leader Bob Moses, who had left the United States to live in Tanzania. He referred me to a friend in Kenya who recommended a rustic cabin overlooking the Indian Ocean. My summer vacation became an extended stay in Kenya. In May 1995, I accompanied an American delegation led by Philadelphia minister Leon Sullivan to the Third African-American African Summit in Dakar, by Abdou Diouf, President of Senegal and Chairman of the Organization of Islamic Conference, and others attending the Third African and African American Summit Meeting in Dakar).  Traveling to the gathering as well as the meetings themselves offered numerous opportunities for conversation with Sullivan and other American representatives, including civil rights activists Jesse Jackson, Al Sharpton, Joseph Lowery, and Dick Gregory. I also reconnected with my former Stanford advisee Susan Rice who had moved to the White House to become Senior Director for African Affairs and a member of the National Security Council. Although I had little to contribute to discussions about increasing American economic ties with Africa, my weeks in Senegal stimulated my desire to return to the continent.

Traveling to the gathering as well as the meetings themselves offered numerous opportunities for conversation with Sullivan and other American representatives, including civil rights activists Jesse Jackson, Al Sharpton, Joseph Lowery, and Dick Gregory. I also reconnected with my former Stanford advisee Susan Rice who had moved to the White House to become Senior Director for African Affairs and a member of the National Security Council. Although I had little to contribute to discussions about increasing American economic ties with Africa, my weeks in Senegal stimulated my desire to return to the continent.

My conversations in Senegal with Mauritanian businessman Abdellahi Yaha would become one of my lasting relationships, resulting in an extended stay in his nation.

I used my Stanford sabbatical year from 2005-2006 to travel to France and teach in Paris at the Écoles des hautes études en sciences sociales (EHESS). After the publication later that year of the German edition of In Struggle, I gave lectures and book signings at Frankfort’s annual book festival as well as in Berlin, Desden, and other German communities.

Soon after the publication of the fifth volume of The Papers of Martin Luther King, Jr. in 2005, my fundraising activities and gift pledges from football celebrity Ronnie Lott and other supporters enabled the King Papers Project to become the endowed King Research and Education Institute. As the Institute’s founding director, I continued expanding my collaborations with scholars and institutions throughout the United States and elsewhere. I also participated in public events with The Dalai Lama, South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu, and Mahatma Gandhi’s grandson Arun Gandhi. Other visitors included San Francisco civic leaders Gavin Newsom and Kamala Harris, civil rights activists such as Jesse Jackson, Dorothy Cotton, John Lewis, James Forman, Julian Bond, Joan Baez, Bernard LaFayette, Fred Shuttlesworth, Andrew Young, Vincent Harding, C. T. Vivian, the Freedom Singers, Mukasa Dada (formerly Willie Ricks), Black Panther leaders David Hilliard, Erica Huggins, Elaine Brown, and many others. King’s former aide Clarence Jones not only visited but decided to become a long-term Scholar-in-Residence at the Institute.

Soon after Morehouse College (Martin Luther King’s alma mater) awarded me an honorary doctorate in history in May 2007, I made my second visit to Beijing where the National Theatre of China and gospel singers from the United States staged well-attended performances of Carson’s play Passages of Martin Luther King. My former advisee Cáitrín McKiernan’s efforts to bring the play to China would inspire her father’s documentary Bringing King to China (2011).

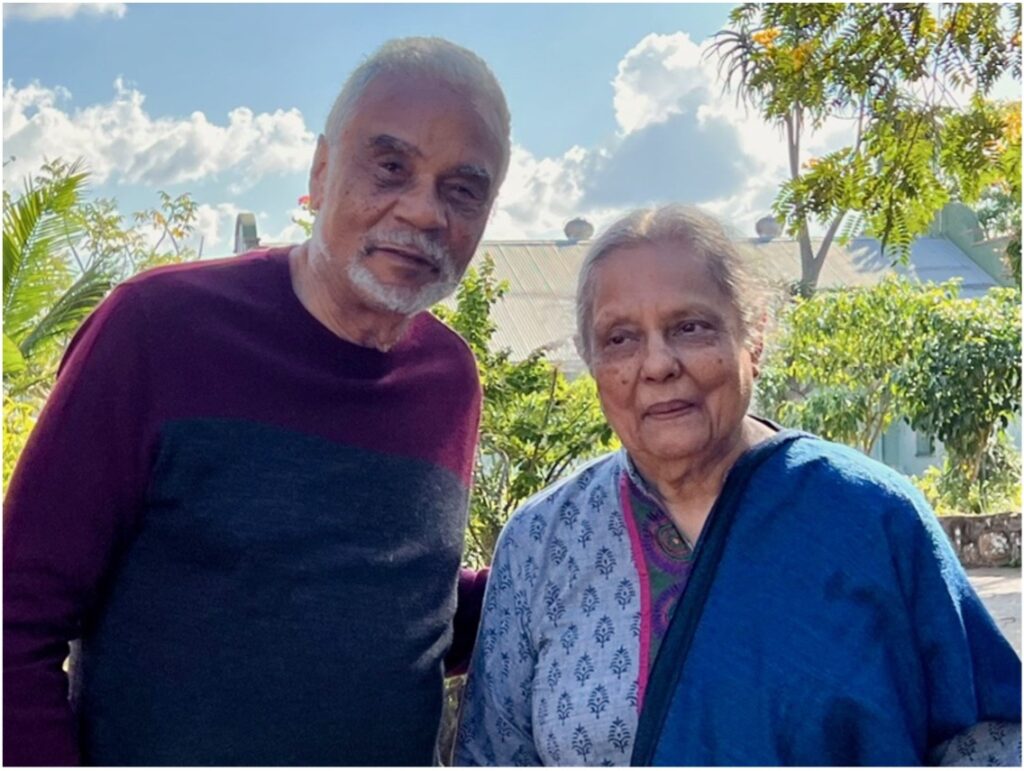

Early in 2008, Gandhian expert Dr. Prasad Gollanapalli visited me at the King Institute, and we pledged to forge stronger ties between Indian Gandhians and American Kingian activists. This collaboration prompted a Gandhi-King course that I taught with Prasad and Stanford scholar Linda Hess. The course in turn led to a three-week Stanford student seminar in India featuring visits to Gandhian ashrams and discussions with Prasad and other Gandhian activists. Early the following year, I commemorated the 50th anniversary of Coretta and Martin Luther King’s visit to India by guiding an official visit to India by a delegation of U. S. Congress members, including former SNCC chair John Lewis, Martin Luther King III, SCLC leader Andrew Young, former Senator Harris Wofford, and other American politicians who met with their Indian counterparts while commemorating the 50th anniversary of Coretta and Martin Luther King, Jr.’s 1959 “tour of the land of Gandhi.”

Early in 2008, Gandhian expert Dr. Prasad Gollanapalli visited me at the King Institute, and we pledged to forge stronger ties between Indian Gandhians and American Kingian activists. This collaboration prompted a Gandhi-King course that I taught with Prasad and Stanford scholar Linda Hess. The course in turn led to a three-week Stanford student seminar in India featuring visits to Gandhian ashrams and discussions with Prasad and other Gandhian activists. Early the following year, I commemorated the 50th anniversary of Coretta and Martin Luther King’s visit to India by guiding an official visit to India by a delegation of U. S. Congress members, including former SNCC chair John Lewis, Martin Luther King III, SCLC leader Andrew Young, former Senator Harris Wofford, and other American politicians who met with their Indian counterparts while commemorating the 50th anniversary of Coretta and Martin Luther King, Jr.’s 1959 “tour of the land of Gandhi.”

My vital contributions to the San Francisco Roma Design Group’s winning proposal in the international competition in 2000 to design the King National Memorial immersed me in extensive discussions with the Memorial Foundation constructing the memorial site. My evolution from a March on Washington participant in 1963 to being a special guest at President Barack Obama’s dedication of the Memorial in October 2011 would become the central theme of my memoir Martin’s Dream: My Journey and the Legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr. (2013).

My vital contributions to the San Francisco Roma Design Group’s winning proposal in the international competition in 2000 to design the King National Memorial immersed me in extensive discussions with the Memorial Foundation constructing the memorial site. My evolution from a March on Washington participant in 1963 to being a special guest at President Barack Obama’s dedication of the Memorial in October 2011 would become the central theme of my memoir Martin’s Dream: My Journey and the Legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr. (2013).

During 2013 my third visit to Israel and the Palestinian territories enabled me to collaborate with the Palestinian National Theatre as it prepared to produce its version of Passages of Martin Luther King. The play became controversial in unexpected ways while it was staged in numerous in West Jerusalem and other predominantly Palestinian communities. The subsequent assassination of the director of Freedom Theater in Jennine was documented in Connie Field’s award-winning film Al Helm: Martin Luther King in Palestine (2014).

The next year, I experienced a highlight of my foreign travels when I accepted the Zambian government’s invitation to be an honored guest at its celebration of that nation’s fiftieth year of independence and to meet with members of its initial government.

By 2015 my objectives had expanded beyond publishing the seventh volume of King’s Papers and instead increasingly focused on the King Institute’s online Liberation Curriculum and classes for teachers. My educational efforts also led to contributions to many documentary films, including God in America: The American Experience Series (2009); Freedom on My Mind (1994), Have You Heard from Johannesburg? (series, 2012, 2018), and El Helm: Martin Luther King in Palestine (2013) by Connie Field; Blacks and Jews (1997), Brother Outsider: The Life of Bayard Rustin (2003), Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence (2010), Freedom Riders (2010) and The Panthers (2015). I also was an executive producer as well as interviewee of I Am MLK Jr. (2018).

My educational activities not only retraced the lives and civil rights activities of Coretta Scott and Martin Luther King, Jr., but also included attending and broadcasting numerous civil rights commemorative events. In 2015, for example, I represented C-SPAN when more than fifty thousand marchers came to Selma, Alabama, to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the historic voting rights march across Edmond Pettis Bridge. I have also led many Southern tour groups of students, teachers, Stanford alums and others seeking to learn more about the civil rights movements of the 1950s and 1960s. My understanding of King’s global impact was greatly enhanced by his visits to places King had visited, such as London, Paris, Berlin, and Amsterdam. I was also an advisor for the King Collection at Morehouse College, the King National Historic Park in Atlanta, the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, and the National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta.

My varied knowledge and accomplishments have been recognized by many international institutions. In 2016, I was invited to participate in the British Academy’s International Conference on Distinguished Documentary Films. Stanford University acknowledged my accomplishments as a scholar and founding editor of The Papers of Martin Luther King by honoring me in 2016 with an endowed chair as Martin Luther King, Jr., Centennial Professor. In November 2018, I traveled to Mumbai, India, to receive the prestigious annual Jamnalal Bajaj Foundation Award for Promoting Gandhian Values Internationally. Carson’s trip to the award ceremony also provided an opportunity for visits to other historically important places in India. These included the Acharya Vinoba Bhave Ashram and the Bajaj Wadi Guest House, once a meeting place for Gandhian revolutionaries.

My varied knowledge and accomplishments have been recognized by many international institutions. In 2016, I was invited to participate in the British Academy’s International Conference on Distinguished Documentary Films. Stanford University acknowledged my accomplishments as a scholar and founding editor of The Papers of Martin Luther King by honoring me in 2016 with an endowed chair as Martin Luther King, Jr., Centennial Professor. In November 2018, I traveled to Mumbai, India, to receive the prestigious annual Jamnalal Bajaj Foundation Award for Promoting Gandhian Values Internationally. Carson’s trip to the award ceremony also provided an opportunity for visits to other historically important places in India. These included the Acharya Vinoba Bhave Ashram and the Bajaj Wadi Guest House, once a meeting place for Gandhian revolutionaries.

In March 2019, I collaborated at the King Institute with a small group of human rights activists who began planning an international Gandhi-King Conference at Stanford to celebrate the 150th anniversary of Gandhi’s birth. The resulting conference in October 2019 was the culmination of similar gatherings held throughout the United States and in other nations.

More than five hundred people attended the Stanford conference, including pioneering Gandhian-American activists James Lawson and Mary King as well as descendants of Coretta and Martin King (Martin III and Yolanda), of Mahatma Gandhi (Ela and Rajmohan Gandhi), and of Delores Huerta and Cesar Chavez (Juanita and Anthony).

After my official retirement in 2019 from Stanford’s faculty, I remained committed to the vision of a global human rights movement that he shared with Prasad Gollanapalli.

After accepting an invitation to join the Center for Democracy Development and the Rule of Law (CDDRL) of Stanford’s Freeman-Spogli Institute for International Studies, I established the World House Project (WHP) and with my colleague Dr. Mira Foster, hosted the annual King Holiday Film Festivals, and taught a Stanford Online multi-media course that received stellar reviews. With my WHP colleagues, I also collaborated with filmmakers Chris Preitauer, Jack Hubbard, and others to produce innovative documentaries for general audiences and weekly courses sponsored by the Oakland-based King Freedom Center. I also collaborated with Dr. Johnny Mack (former director of Martin Luther King III’s Realizing the Dream project) to teach an online human rights course and moderate weekly meetings of the World House Global Network.

In June 2023, I delivered the keynote address for the Gandhi-Mandela-King International Conference in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. Inspired by the King Institute’s 2019 Gandhi-King conference, this gathering commemorated the 130th anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi’s life-changing vow in Pietermaritzburg to formulate an effective nonviolent strategy to resist injustice. I also used this opportunity to meet in South Africa with veteran activist and WHP participant Ela Gandhi at Phoenix Farm, which was inspired by the human rights community founded by her grandfather many decades earlier.

Soon after returning from South Africa in June 2023, I suffered a cerebellar stroke that damaged my balance control and required more than a month of rehabilitation. Realizing that my physical capabilities were limited and that Stanford funding for the World House Project was expiring, my colleagues and I have continued our online teaching with adults and students affiliated with the King Freedom Center based in Oakland, California.

They have previewed the WHP’s future direction by shifting its focus beyond the modern American civil rights movement to incorporate the broader history of global human rights activism. In addition to resuming my lecturing, writing, and other scholarly activities, I also traveled in October 2023, to Memphis, Tennessee, to join Stacey Abrams and Kerry Kennedy as recipients of the National Civil Rights Museum’s annual Freedom Awards.